A striking illustration of the staff’s targeted deployment of its resources to achieve maximum effect was Sporkin’s decision to focus on gatekeepers, the professionals who are indispensable for issuance and trading of securities. Under Rule 2(e) (now 102(e)), the Commission long had the power to discipline professionals (almost always lawyers and accountants) who appeared or practiced before it, but before the 1970s it chiefly targeted marginal individuals who were “active participants in blatant frauds.”(1) That approach changed under Sporkin, who pushed what he called the “access theory.”(2) According to Sporkin, “[w]e knew we would always be strapped for personnel. And so we had to develop a strategy that would help us stretch our enforcement dollar as far as it would go. And in this regard we developed the so-called access strategy . . . . The theory was that we didn’t have the resources to police every crooked promoter. . . . But we could narrow down our looking to a very small group of professionals who provide access to the marketplace.”(3) In the 1970s the Division brought enforcement actions against major accounting firms accused of aiding client frauds – Daniel Hawke reports that six of the “big eight” firms were targets of proceedings during the decade(4) – but even more bold was the SEC’s new willingness to target lawyers.

In early 1972 the SEC filed an enforcement action against National Student Marketing (NSM), a conglomerate targeting the college market that was eventually found to have committed accounting fraud to conceal faltering growth. What surprised the securities bar was that the SEC brought actions not only against NSM, but against lawyers from well-known law firms advising on an NSM acquisition, New York’s White & Case and Chicago-based Lord, Bissell, and Brooke. “For the first time old firms of recognized competence and integrity were named as defendants.”(5) In not correcting their client’s misrepresentations concerning the acquisition, the SEC alleged, the lawyers had violated the antifraud rules.(6) While lawyers were never allowed to aid a client’s fraud, the charges seemed to impose a new responsibility: to withdraw and, if necessary, to disclose the client’s fraud.(7) NSM produced an uproar; after the charges were brought, one Washington lawyer claimed that “securities lawyers are shaking in their boots.”(8)

Nor was NSM an isolated case; through the rest of the 1970s both law and accounting firms found themselves under new scrutiny from the Division. A few months after the NSM complaint, the SEC sued fugitive financier Robert Vesco for looting mutual funds he controlled, again naming partners of a prominent New York firm, in this case Willkie, Farr & Gallagher.(9) In the eyes of its defenders, this approach was what the Enforcement staff did best: levering limited resources and legal imagination to work larger change. To its critics, it was stretching the securities laws in unprecedented ways.(10) Despite the criticism, the Enforcement Division persisted in targeting gatekeepers, bringing over 120 2(e) cases during the 1970s; in previous decades, it had brought fewer than ten.(11)

(1) Lewis D. Lowenfels, Expanding Public Responsibilities of Securities Lawyers: An Analysis of the New Trend in Standard of Care and Priorities of Duties, 74 Colum. L. Rev. 412 (1974); Roberta Karmel, Attorneys’ Securities Laws Liabilities, 27 1972 Bus. Law. 1153, 1156 (1972).

(2) Sporkin, “SEC Enforcement Practices,” quoted in Hawke: 27; John Coffey, Gatekeepers: The Professions and Corporate Governance: 108-245 (2006).

(3) Stanley Sporkin oral history: 11-13.

(5) A. A. Sommer, The Emerging Responsibilities of the Securities Lawyer, Thursday, Jan, 24, 1974.

(6) Complaint for Injunctive and Other Relief, SEC v National Student Marketing.

(7) Wallace Timmeny, Responsibilities of Lawyers in Connection with the Sale of Municipal Securities, 36 Bus. Law. 1799 (1981).

(8) A Bid to Hold Lawyers Accountable to Public Stuns, Angers Firms, WSJ Feb. 15, 1972: 1.

(9) SEC Files Big Civil Suit Against International Controls, Vesco and 40 Others on Charges of Draining IOS Funds, Wall St. J. Nov. 28, 1972: 3; see also Ted Sonde oral history: 16.

(10) Karmel, Attorneys’ Securities Laws Liabilities, 27 Bus. Law. at 1153.

(11) Roberta Karmel, Regulation by Prosecution: The Securities and Exchange Commission versus Corporate America: 145 (1982).

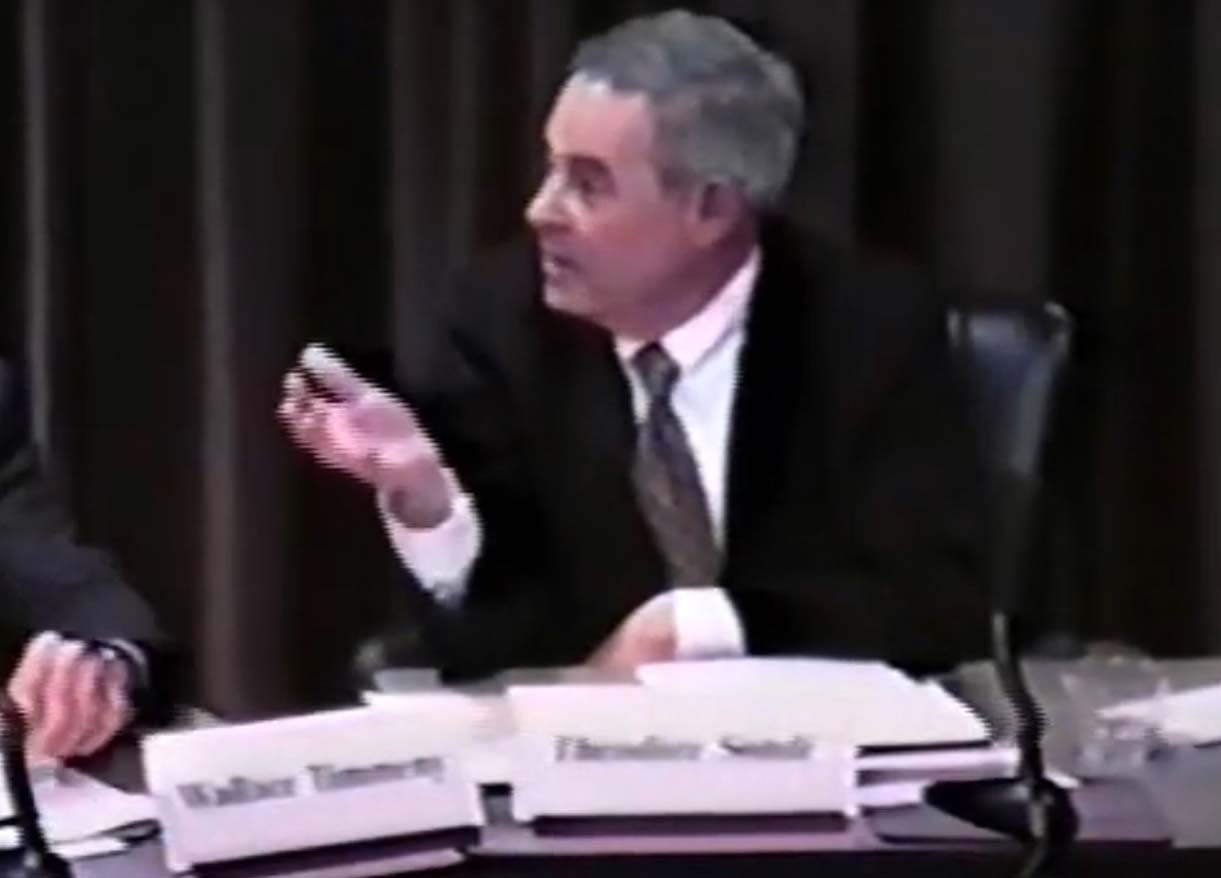

Wallace “Wally” Timmeny served in several positions at the SEC from 1965 – 1979, from assistant director in the Criminal Reference and Special Proceedings unit of the Division of Trading and Markets under Irving Pollack to Deputy Director of the SEC’s newly-created Enforcement Division under Stanley Sporkin. During his tenure, he led the SEC’s early efforts to combat municipal securities fraud, was a key player in the Enforcement Division’s famous “voluntary program,” and had first-hand experience with Sporkin’s ‘access theory’ regarding the role of lawyers, accountants and other ‘gatekeepers’ in enforcement cases.